- Home

- Tim Standish

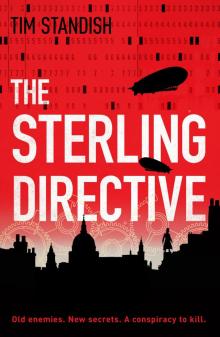

The Sterling Directive

The Sterling Directive Read online

About the Author

Tim Standish grew up in England, Scotland and Egypt. Following a degree in Psychology, his career has included teaching English in Spain, working as a researcher on an early computer games project, and working with groups and individuals on business planning, teamworking and personal development.

He has travelled extensively throughout his life and has always valued the importance of a good book to get through long waits in airports and longer flights between them. With a personal preference for historical and science fiction as well as the occasional thriller, he had an idea for a book that would blend all three and The Sterling Directive was created. Tim sees this as the first in a series of novels featuring Agents Sterling and Church (and almost certainly Patience). He is already working on the second book, which will be set in America and reveal more of the alternative history of Sterling’s world.

When not working or writing, Tim enjoys long walks under big skies and is never one to pass up a jaunt across a field in search of an obscure historic site. He has recently discovered the more-exciting-than-you-would-think world of overly-complicated boardgames.

The Sterling Directive

Tim Standish

This edition first published in 2020

Unbound

T C Group, Level 1 Devonshire House, One Mayfair Place, London W1J 8AJ

www.unbound.com

All rights reserved

© Tim Standish, 2020

The right of Tim Standish to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-78965-086-0

ISBN (Paperback): 978-1-78965-085-3

Cover design by Mecob

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

For my parents

Contents

About the Author

Dedication

Super Patrons

Prologue

London. 1896.

1. Smoke

2. Rendezvous

3. Mesh

4. Panopticon

5. Sound

6. Ghosts

7. Patience

8. Whitechapel

9. Call

10. Illuminations

11. Arpeggio

12. Dresser

13. Fox

14. Frame

15. Rag

16. Cowboy

17. Bustle

18. Trip

19. Local

20. Springheels

21. Mapmaker

Acknowledgements

Patrons

Super Patrons

Alistair Armit

Margaret Ayers

Jason Ballinger

Anthony Browne

Kate Bulpitt

Finnian Clark

Jo Clark

Nick Clark

JJ Cowan

CSF Marine Consulting Ltd

Cassy Ede

Philip Eve

Esme Godden

Patrick Goodall

Anton Gorostiaga

Richard Gray

Simon Haslam

Michael Hurwitz

Lucy Johnson

Sarah Jones

Nick Lang

Sian Lang

Pete Langman

Mary Ann le Lean

Donna Lelean

Elizabeth LeLean

Hannah LeLean

Jeremy LeLean

Joseph LeLean

Les LeLean

Maureen Lelean

Paula LeLean

Terry Lelean

Chris Limb

Ethan Maltby

Jonathan Massey

Janice McGuinness

Megan Meredith

Alan Mitchell

Sean Moore

Kate Newton

Mike Nugent

Mark O’Neill

Andrew Park

Dan Porter

Jason Reid

Martin Roche

Richard Ryan

Les Sharman

Louise Sheridan

Dan Shlepakov

Dan Simpson

Naomi Simpson

Cindy Vallance

Sonja van Amelsfort

Edwina Waddy

James Whittingham

Steve Wilinsky

Stephen Wren

Anita Wyatt

Prologue

The early engines were huge, cumbersome warehouses of rods and cogs, too complex and expensive for any but states to own and operate. Hence their operations largely consisted of the collection, codification and analysis of data, with the overall aim of protecting and sustaining the longstanding status quo. Government agencies such as Britain’s Bureau of Engine Security closely guarded the secrets of engine technology, keenly punishing its illegal use.

It was not until the final decades of the century that engine technology became cheaper to produce, more portable and more accessible to a wider marketplace of inventors, manufacturers, researchers and, inevitably, the criminal classes. From this seething pot of experimentation bubbled not just technological, but societal and even political changes as old mores and certainties were challenged and disordered.

In Britain, Gordon of Khartoum swept to power at the head of a new political movement whose continental sloganeering of equality and brotherhood unfortunately proved unbeatable. Despite its reduced circumstances, France’s pre-eminence in the new battleground of on-wire engine warfare cemented its place as a player in the great game; and Paris’s reputation as an infamous haven for tappers and data brokers is well deserved. Even the Confederate States of America, long shunned because of President Jackson’s actions in the Second Civil War, found its way slowly back into world affairs, the commercial possibilities of new, connective technologies breaching the walls of political isolation.

The 1880s then, and even more so the 1890s, proved to be the beginning of a new era: the Age of the Engine.

– Maria Corelli, A Young Woman’s History of the Modern Age (1908)

London. 1896.

1. Smoke

‘Gentlemen. Before we proceed I must ask you both whether you are willing to resolve this dispute by any other means?’

The fog that clung to the concrete surface of the platform was given a pale glow by the first light of an early dawn; Burns, my second, could barely be seen where he stood, scarf wrapped across his face, in the shadow of a black iron pillar some way beyond me, a little further than the distance I would have to walk. It said much about the length of my absence from London society that the only support I could command in such a venture was the man known about the club as ‘Secondary’ Burns, a man who had, to my knowledge, offered his services as duelling assistant to eight of our fellow members, each and every one of whom had subsequently been unsuccessful in their aim.

No wordplay intended.

‘Very well. On the count of one, you will each take a step in the direction you are facing. At each subsequent count, you should take an additional step until the count of ten is reached. At that time each of you will turn and fire a single shot at his opponent. If as a result either of you has been mortally wounded, or if honour is otherwise deemed to have been satisfied, the exchan

ge is complete. If, however, these conditions are not met, you will reload and continue to fire until that is the case. Do either of you not understand these instructions?’

Somewhere between where Burns was standing and where my final pace would take me there was an empty cigarette packet on the ground, but from where I was I couldn’t tell the brand and, for some reason, this suddenly seemed oddly vexing.

The station official waited a sensible amount of time for either second to voice a concern or query. Both remained resolutely silent. The official nodded to the doctor who stood off to one side and, after one last enquiring glance to each party, continued.

‘Very well. ONE.’

The thought occurred to me as I set off that, if I stretched my strides slightly, I would be able to reach a point where I would be able to make out the lettering on the cigarette packet. I adjusted my pace accordingly, but stepped carefully; a heavy frost still lay, unmelted, on the platform’s surface.

‘TWO.’

The trouble was that the few brands available prior to my departure had, since I had been away, been joined by a proliferation of new cigarette brands which, in an attempt to win favour with the short-sighted purchaser, had based their design on those of the established manufacturers. Somewhere on one of Waterloo’s other, functioning platforms, an early service from Paris hissed to a halt, whistling its arrival cheerily. I imagined newspapers being folded, cases grasped, coats donned, hats carefully seated on heads.

‘THREE.’

The industrialisation of London seemed to have grown apace, with smaller engines appearing to be more commonplace than they were when I left for America. The military had of course retained the monopoly on the more complicated engines, the specifications of which were still secret. However, partial declassification of the technology involved had led to many smaller companies being able to compete beyond their natural reach and had instigated a commercial revolution. At least that was what it had said in the in-flight magazine that I had glanced at on the way over from Canada. From what I had seen of London so far it seemed mainly to mean: more smoke.

‘FOUR.’

The name was Victoria… Or perhaps victory. Either would make an obvious title for a patriotic brand of tobacco.

It made me think of one of the first patrols I had undertaken in my posting; my section had come across a little village, barely more than a collection of shacks and lean-tos and almost certainly inhabited by the French speakers who populated that area of the Canadian Provinces.

‘FIVE.’

Given what we’d been told about local sentiments I had been astounded to discover an almost life-sized picture of Her Majesty adorning the largest hut. I mentioned this symbol of heartening patriotism to my sergeant, a veteran of the region who responded to my question with a short laugh. ‘Bless you sir,’ he said ‘that’s the name of the gin they make round here.’

‘SIX.’

Some weeks afterwards I was informed by a fellow officer that I had acquired the nickname ‘Ginny’ Maddox. It was the last time that I had hazarded an opinion about the locals in earshot of my sergeant.

Something buzzed sharply past me and I was puzzling over its source when the sound of a shot echoed through the platform. Pausing in my stride I cautiously put a hand to my shoulder and it was only when I saw it covered in a bright smear of blood that I realised what had happened. I was about to turn when another sound distracted me. I looked ahead and saw Burns collapse, gasping, to his knees. I turned to the official who had begun proceedings.

‘If you will continue counting, sir.’

‘But… I mean… I—’

‘Continue the count, if you please.’

‘SEVEN,’ the official continued, more uncertainly than before.

I recommenced my pacing, feeling the pain and warmth spread out across my neck and shoulder as blood began to slowly seep into the cloth of my jacket.

‘EIGHT.’

Over the years an increasing number of rituals and restrictions had been crafted to differentiate what happened at the Waterloo duelling grounds from the more common act of murder as practised by grubbier protagonists in the rest of the capital. One of these, the embargo against weapons produced after 1815, lent a confidence to my careful pacing that I might not have felt had we been using modern pistols.

Even so, the percussion pistols deemed ‘quite the thing’ by fashionable society this season were one of the most sophisticated styles available and, though still fiddly, were relatively quick to load. As I stepped out the remaining two yards I ran through the reloading actions in my head, estimating that my opponent’s nerves would provide enough time for my remaining two strides.

It occurred to me that, while being shot once from behind said something about the baseness of the shooter, being shot twice from the same direction spoke more badly of me.

‘NINE.’

Burns was on all fours, pawing the ground, trying to lift himself up; his breath spouted in steaming gasps from his mouth. His face, as far as I could make out, seemed more puzzled than in pain.

I was close enough to see the packet clearly now. Victoria. The engine-stippled design rendered her majestic and unsmiling in a pose long since unrepresentative of her ailing health.

‘TEN.’

I turned. Edgar had his back to me, struggling along with his second to reload the pistol. ‘Edgar!’ I called down the platform.

The Honourable Edgar Theodore Huntingdon looked round, his face white against the black of his second’s hat brim and time slowed, sound faded. I remembered him in our staircase at college, loudly confident, dismayed at our lack of enthusiasm for midnight carolling. And in London, determinedly the bon vivant of our set, dragging us all to the latest and brightest places. And in Cooper’s. Always back to Cooper’s.

I raised my arm and sighted, my breath clouding in the freezing air, held the gun steady, gently pulled the trigger and felt that guiltily reassuring kick of the gun’s blast. The cloud of smoke obscured my view and the gun’s blast froze my hearing but I knew instinctively that I had hit.

I sidestepped for a clear view and I saw not only Edgar, but also his second seeming to hang for a moment as a faint red mist clouded the air around them both.

Hearing returned, breathing began and my senses quickened. The two men collapsed to the floor.

The first time I killed a man was in Canada; our camp had been attacked one night by a small force of outlaws from across the border. Awakened by the sound I raced to the perimeter and began shooting into the darkness, aiming at nothing, just wanting to show my men that I was no stand-off officer.

We had fought the attack off and at first light I went out with my sergeant to check the bodies. We came across one lying not far from the section of the stockade I had helped defend. He had been shot in the stomach and was barely alive. Sergeant Jones had bent down to him and looked up at me. ‘The poor bastard’s got his lights hanging out, sir. He’s done for.’ He had told me, ‘Best finish him off.’ He had smiled at me and nodded in what he had probably thought was an encouraging manner.

I had looked down at the man’s face. He was a thuggish-looking fellow with a bristled, coarse face. One of the criminals periodically set free to harass us at a long and deniable arm’s length by the Confederate States. I had drawn my pistol and pointed it at the man’s face then pulled the trigger with my eyes half shut. Jones had clapped me on my shoulder and had walked towards where another body lay with me in tow, a chick to his mother hen.

I had managed a few yards before doubling over and vomiting. The sergeant had tugged me to my feet, muttering ‘better out than in’ and suggesting that perhaps I might like to leave the rest of the perimeter to him. I had wiped off my mouth, drawn in a breath and replied that I was happy to continue; stern faced and with a semblance of composure I had done just that, enduring Jones’ gruesome commentary as we were touring the ground. By the end of the circuit I had even managed a laugh or two that had seemed to result in a grud

ging few points being added by him to my meagre tally of respect.

That night I had lain under cold, stiff canvas, curled in my cot like a child, and prayed for sleep.

Now, eight years later, as I stood looking at the body of a man I had once counted my closest friend, I watched a dark stain spread from a hole in his chest and I felt nothing.

The man who had acted as our official walked towards me even as the attendant doctor rushed to confirm the inevitable.

‘I really must congratulate you sir, not only on your bravery but moreover most deservedly on your marksmanship. Really, I am quite astounded to have witnessed such an exemplar of gentlemanly conduct. Next time I hear someone say that there are no old-fashioned officers left in the army I’ll be sure to point out their error. I dare say that here’s one pair of overprivileged layabouts that have been persuaded of that.’ He barked a little laugh and beamed at me as if waiting for applause.

I looked at him. Handed him the gun without a word and stared at him in silence until uncertainty began to creep across his face.

‘Make sure someone attends to him,’ I said tersely. ‘I would take any ill feeling toward him as if it were directed to my own person and consider myself obliged to act accordingly.’

‘Please… I meant no disrespect… of course I shall ensure all arrangements are conducted most carefully,’ he stammered out, fear competing with obsequiousness for prominence on his face. He would no doubt be in the offices of some Fleet Street hack before Edgar was lying cold in the mortuary.

He reset his face to ‘respectfully solemn’ and waited for me to commend him on his show of respect. When no such affirmation was forthcoming he haltingly broached the main reason for his approach.

The Sterling Directive

The Sterling Directive