- Home

- Tim Standish

The Sterling Directive Page 2

The Sterling Directive Read online

Page 2

‘Captain. The matter is… er… the second of the deceased gentleman on such an occasion usually vouchsafes any… er… monetary transfer that should prove necessary. As the young man in question is sadly… er, I wondered if… er… that is to say—’

‘See that any expenses incurred are forwarded to me.’

‘And, er, Captain if you don’t mind me asking, the other, er, gentlemen? Should I include them on your account?’

I looked down at Edgar’s second, whose face had been smashed into bloody ruin by the pistol’s ball. ‘By all means add this one, but,’ I turned back to where Burns was lying face down on the stones of the platform, ‘I feel disinclined to pay for a second who doesn’t have the decency to shout a warning. Here.’ I fished a card from my tunic pocket and handed it to him.

He took the card. ‘Quite understandable, Captain, many thanks. I just need to check the available funds, if you wouldn’t mind waiting here. I’m sure you understand. Thank you so much.’

He walked as quickly as decorum would allow to his office at the far side of the platform where through the window I saw him bend to insert my card into an old-fashioned-looking reader on his desk. Face pressed close to the display, he impatiently drummed his fingers while he waited for the message to travel to and from the bank’s engine house. He glanced up, saw me looking at him and returned his gaze to the machine, probably unbelieving that a mere Captain, no matter how gentlemanly, could afford the services of the London Necropolis Company. I reached up to my head, which had begun to throb and found the blood already sticky. Not deep but hurt like the devil.

I heard something behind me and turned. Edgar was still alive, trying to raise his head. I stepped to where he lay, and knelt. The ground behind him was soaked with half-frozen blood. His eyes tried to focus on me; his lips moved almost silently. I bent to hear the words he was hoarsely forcing out between gritted teeth.

‘Charl. Char. Charles.’ He took a ragged breath. I’d seen men like this, desperate to cling on to the breath even as it leaked from them. ‘Luh. Lucky. Lucky ba… bastard.’ He tried to smile but it was beyond him. His eyes changed, the light leaving them as he tried one more time. ‘So. Sorry. Charles. Not my fault. Fuh. Fuh.’ He choked and coughed a thick lump of blood onto his chest. A tear started its slow way down his cheek. ‘Less.’ He grunted with effort to form the word, and I realised he was saying Alice. A flash, then, of wet, red memory. The taste of bile in my mouth. I swallowed both away.

And watched as Edgar stopped talking, and then, simply, stopped.

Oddly, though this very moment was one I had imagined and wished for, especially in the early years of my exile, I found myself curiously devoid of sorrow or anger or vindication or any other emotion. Just empty and tired, standing in the cold on the International Platform at Waterloo, and very suddenly aware of the dull but persistent ache in my shoulder.

I stood, straightened my tunic and turned to where the official was returning with an odd look on his face.

‘Sir, my Lord, I had no idea of course or I would never have assumed, that is to say of course there is no issue of credit insofar as your lordship is concerned. Most humbly pleased to be of service of course sir, that is, er, my Lord.’ He proffered a clipboard with a printed form and handed me a pen.

As I read it my breath caught in my throat. The name that I should have been reading was the name I had travelled here from Canada under, the name of a humble captain in an unfashionable regiment. In fact, my real name was printed out as plain as day: The Hon. Charles Arthur Maddox. In haste I had given him the wrong card. Suddenly nervous I looked about the platform that was, of course, still deserted at this time in the morning.

‘The London Necropolis Company thanks you for your patronage my Lord and hopes that you use us again for any funerary needs you may have in the future.’

I smiled uncertainly, signed the form. He handed back my card and I tucked it away in a pocket. In my mind I imagined engines turning their gears, my name appearing with a click, lighting a light on somebody’s desk. I took one last look round the platform, nodded curtly to the official and to the doctor bent over the bodies of Edgar and his second.

‘Gentlemen.’

I hurried towards the platform exit where a Metropolitan Police sergeant and a garde impériale waited to check my pass. I took it from the same pocket that held the card I should have used and handed it to the sergeant, whose three stripes were brightly picked out in silver thread upon the collar of his overcoat.

He unfolded the pass and studied the printed likeness carefully, concentration furrowing his brow, before glancing at the rest of the paper.

‘A monthly, sir?’ he observed as he looked up, the surprise in his tone causing his colleague to take more of an interest. ‘You’re not expecting to be back here again are you?’

‘I had no expectation of being here in the first place, sergeant and I sincerely hope that the business is now concluded, but I always remember something I was told by an officer I once met.’

‘Really sir?’

‘Yes, we were at dinner one evening and he was asked to say what, in his opinion, was the single most important skill for a soldier to have.’

‘And what did he say that was, sir?’

‘To be prepared, sergeant, to be prepared.’

He laughed indulgently, his French colleague joining in after a moment’s delay. ‘Very good, sir. A very sound piece of advice I’ve no doubt. Well, this all seems to be in order.’ He refolded the paper and handed it back. ‘And may I say a fine piece of shooting on your part.’ He smiled for a moment and then seemed to remember his role. ‘Just make sure you keep that sort of thing in here on the platform.’

‘But of course.’

‘If I may point out, sir, you really ought to have that injury seen to. Might just be a lucky graze, but you can never tell with these old pistols. If you will allow me to call you an ambulance…’

I nodded and he led me into the station proper. We had reached the stairs leading down from the entrance to the road where a few ambulances, guessing a duel was on or, more likely having been tipped off for a few shillings, waited for fares.

‘Ask one of those chaps to take me to the hospital at Charing Cross would you?’

‘Right you are, sir.’ He smiled, a customer of Charing Cross could be expected to furnish an appropriately large gratuity.

‘Oh, and sergeant!’

He looked up from mid-negotiation. ‘Sir?’

‘Tell him he’ll be waiting for me there and then taking me on to an hotel.’

‘Right-o, sir.’ I felt in my pocket for a coin.

From the main entrance to the station the earliest of the day’s commuters bustled on their way to work. London was beginning to stir.

2. Rendezvous

The room’s kinetographic screen was mechanical, and every time an image changed it did so with a cascade of minute ripples from the top to the bottom of its ornate silver frame. I had only found one channel that wasn’t pornographic; a short, repeating visual summary of the day’s headlines. A parade of Indian troops receiving medals, Salisbury leaning tiredly at the dispatch box, Gordon at a rally, the crowd festooned with placards, a well-dressed young couple hugging in front of a set of steps, Vice-President Custer and his wife arriving at Croydon Aerodrome; each image fluttered into being for a short time, the bottom half of the screen showing the relevant headlines. A dozen or so others went past and then, just as I was beginning to feel relieved, the screen showed an image of Waterloo Station with the words ‘Mystery Toff Tops Two!’ emblazoned beneath.

I silently cursed my stupidity and pressed the buttons that switched off the screen, causing it to ripple for one last time, the pictures vanishing from top to bottom, leaving the surface within the frame a dull grey.

‘You don’t like the girls, Milord?’

I turned to face her. ‘Of course I do.’

‘You like Marie?’

‘But of course.

’

‘I think the Madame will be here soon, but maybe we have time for a little game?’ She turned to lie half back on the bed, the heavy velvet robe slipping as she did so to ‘accidentally’ expose a most non-demure expanse of pale skin. She cocked her head invitingly and settled back into the silk pillows, shrugging the unfastened hems of the robe further apart as she did so.

I watched this perfectly rehearsed routine and, despite myself, felt it beginning to have an effect on me, despite the fact that I had seen it, with subtle variations on countless previous occasions with the other Maries I had met here in this room.

She was, I thought to myself, ever so slightly shorter than the last Marie I had known. In all other respects, though, they were identical; the same pale golden skin, long raven hair and slightly angular features framed by the same clothing, make-up and setting. I had known three different Maries here, with this version a fourth and there may well have been others while I was away in Canada. However, everything was engineered to exaggerate the effect so that one could, with very little effort, imagine that on every visit, the same, unchanging girl was to be found waiting, alluring in her red velvet robe.

It was the same in every room in Cooper’s, the same process of illusion repeated, though with different themes in each. I had never chosen an Emily or a Pilar, a Mariko or a Heidi, but if I had done so, I would have known precisely what to expect. Mrs Cooper prided herself on her ability to consistently provide for her clients’ expectations, an intention echoed by the portraits that hung above the staircase at the front of the house, each in the style of a different artist and each portraying one of the girls au costume. This gallery acted as a sort of catalogue for visitors to the house, an artistic promise of what lay in store. Some customers cycled through the rooms as the whim took them, but I had always remained loyal to Marie from the very first time I saw her. And, as I watched her now, it was reassuringly easy to suspend my disbelief and believe that this was my dear sweet Marie, waiting through the long, lonely years for my return.

But nostalgia was only a small part of why I was waiting here at Cooper’s, rather than sensibly staying in my hotel room until it was time to head to Paddington to catch the sleeper. Killing Edgar had been foolish and with him dead the only person who might give me the answers I needed was Mrs Cooper. I looked at my watch; almost five o’clock. Another thirty minutes before I would have to leave.

Perhaps taking my clock-watching as indifference, Marie chose that moment to roll entirely out of the robe and to lie, nude, on the bed, with her arms above her head, legs drawn up and turned to one side, her head gazing upwards as if unaware of the effect she might be having. Unhampered by the velvet, her perfume drifted languorously across the room. I could not think of a single soldier who I had served with in the last eight years who would not have thought this a dream come true.

And then, unbidden, that long-submerged image pressed itself briefly into my mind again and for slightly longer than an incoherent flash this time: another room here in Cooper’s, with another girl lying on a bed of scarlet. Any thoughts of taking up Marie’s offer drained from me in a moment. I forced the memory back down and mustered a thin smile.

Puzzled and not a little irate at my failure to respond to her invitation, Marie tried another pose, lying face down with one leg bent up and head turned to with a playfully beckoning glance. I intervened before I was treated to a series of staged variations on the theme of ‘coquette’.

‘I say, Marie, why not order some champagne for us?’

She paused, giving the appearance of deep pondering. ‘And per’aps some chocolat, Milord?’

‘Some chocolat would be perfect, Marie.’

She wrapped herself back up in her robe, jumped up from the bed with girlish glee and skipped to the panel of buttons set next to the door. ‘Just the drink?’

‘A little to eat, perhaps; you choose.’

She gasped (just a little too) excitedly and opened the book; started punching in combinations of numbers.

‘Careful now, m’dear,’ I called, ‘I’ll have nothing left to pay you with!’

She half turned to me, eyebrows raised, clearly unconvinced by this assertion and continued to tap a series of numbers into the controls. Before she had finished, a gentle chime sounded and a small blue light went on over a discreet panel set into the wall near to where she stood. She slid it up and reached in to gather up the tray of drinks that had appeared. She brought it over to the table near the window and set it down before settling down in one of the armchairs, feet drawn up and red velvet gathered around her, waiting expectantly for me to finish filling the glasses.

I tugged the already opened bottle from the ice bucket and began to pour. She seemed genuinely excited to be about to drink champagne and I idly surmised that she must have only recently arrived at Mrs Cooper’s if champagne was still such a treat for her.

And smiled to myself at how easily I had been taken in with what was a part of the act, the story that went with Marie. I handed her a glass, which was rewarded with a gasp, a smile and a ‘Merci beaucoup, milord’. As I watched her sip prettily, her story came back to me.

A recent arrival from Paris, Marie had always ‘just arrived by train the night before’ in flight from French Imperial agents who had arrested her parents. She was always hungry and always thirsty and always ever so grateful to a kind gentleman who would buy her a glass of champagne and a cup of hot chocolat. Her command of English was moderately poor, always spoken with a sweetly continental accent and she was especially keen to learn any new words she might be taught. I picked up a flute of champagne and toasted Mrs Cooper in silence.

‘Madame will be ’ere soon, Milord.’

It was the first thing that Marie had said to me when I had arrived to find her waiting for me downstairs and was a phrase that she had repeated several times in the hour since. ‘I hope so,’ I said, and sipped the champagne which was, of course, as fine as the surroundings.

I decided to wait it out a while longer. Mrs Cooper was someone I had thought about long and hard during my time away as I tried to fathom why she had acted as she had that night eight years ago. Edgar’s motive was plain; he wanted me to take the blame for what he had done, but why had Cooper helped him rather than me?

‘You like some music, per’aps?’

I nodded and Marie went across to the phonogram, plucked a cylinder seemingly at random and dropped it in. A tune of arabesque origin began to drift about the room, and I lay back in my chair, and tried to relax. Not an easy task; although I wasn’t named as the ‘Mystery Toff’ in the headline, I was unconvinced that my anonymity would last for long and wanted to get out of the capital as soon as possible. But I needed to speak to Cooper, to hear her version of our last meeting here.

There was another low chime, the light came on again and Marie skipped across to the panel to retrieve a tray of what turned out to be pastries and fine chocolates.

This tray went on to the bed, while she brought a plate of pastries across and sat, with them, on my lap.

‘Milord?’ she offered me a pastry and, finding myself hungry, I nodded. My stomach agreed, gurgling as I swallowed the first bite, an easy cue for a hands-in-the-air gasp and shriek of laughter from Marie. ‘You must have all of these, I think, you are so ’ungry. I will get some more for us.’ She left me the plate and went back to order more food.

‘You are a soldier, Milord?’ she called back over her shoulder.

‘What makes you say that?’

She looked up from the panel of buttons and shrugged her shoulders.

‘I was.’

She came back and sat on the edge of the bed nearest me. Her legs swung slightly. ‘Did you ever kill a man, Milord?’

I looked at her and adopted what I hoped was a serious expression and shook my head.

‘Never.’

She frowned. ‘You must be a bad soldier, Milord.’

‘The worst that there is. I couldn’t hit a barn do

or if my nose was touching it.’

She thought about this for a moment, either working out what this meant or doing a good show of working it out and a smile slowly appeared. She tilted her head and narrowed her eyes. ‘I think you are joking me, n’est-ce pas?’

I laughed. ‘Un peu.’

Her eyes widened, delighted. ‘Vous parlez le Francais! Très bien!’

I assured her that this was not the case, that I only spoke a little French and that badly but she insisted on continuing the conversation in French, by turns complimenting me on my grammar and mocking my accent which, like the language itself, had been picked up in Canada. Then she wanted to know about Canada and I told her about the cold, the wilderness and the sporadic fighting. We drank champagne as we talked. Were there any women there, she wondered. None as pretty as she, I assured her.

Again the laughter and this time she came to sit in my lap again and rewarded me for my compliment with a gentle kiss on the forehead, and on the nose and on the lips, and then it was no longer gentle and her hands were round my neck and, suddenly light-headed, it took every effort on my part to lever her away. She looked at me calculatingly.

‘Some more champagne, Milord.’ It was not a request and this time she paced languidly to the door, the red robe trailing behind her so that when she turned to order another bottle, the curves of her profile were alluringly visible. I exhaled slowly and took a deep breath in, shaking my head, and got up, sliding the window upwards to let in some fresh air.

And paused.

‘Milord?’ Marie was behind me; I heard the robe fall to the floor and felt her hands on the back of my neck.

‘Hush.’ I shrugged her hands off, ignoring her, and moved so that I could see out of the window, down into the square outside. It was empty; a street sweeper walked across the small park in the middle, a small white dog trotting after him.

‘Qu’est-ce que c’est?’

I turned to face her. ‘I don’t know. Put out the candles and stay back from the window.’

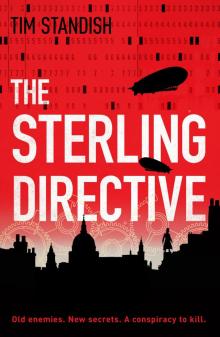

The Sterling Directive

The Sterling Directive